Biden’s cybersecurity legacy: ‘a big shift’ to private sector responsibility

Cybersecurity policy under the Biden administration has been marked by a dramatic shift: a stated strategy over the past four years to transfer the burden of protection from consumers to those most capable, particularly the private sector that makes the technology and owns the most vital infrastructure.

It’s a sweeping change that’s still underway across the 16 critical infrastructure sectors prioritized for federal protection, covering offices from the White House to the Federal Housing Administration. This effort has led to regulations establishing minimum security standards in new areas, supported by various voluntary efforts.

The change has encountered criticism in that it’s both gone too far and not far enough. Regardless of the upcoming election’s outcome, some aspects are likely to remain. If Vice President Kamala Harris is elected, continuity along the current path is expected. If former President Donald Trump wins, the Republican platform has vowed to “raise the Security Standards for our Critical Systems and Networks.”

It’s a path with an uncertain future in other regards, however, based on the ambiguity of agencies’ regulatory power in the aftermath of a key Supreme Court ruling. Already the courts have proven a hurdle in one critical area: the vulnerable water sector.

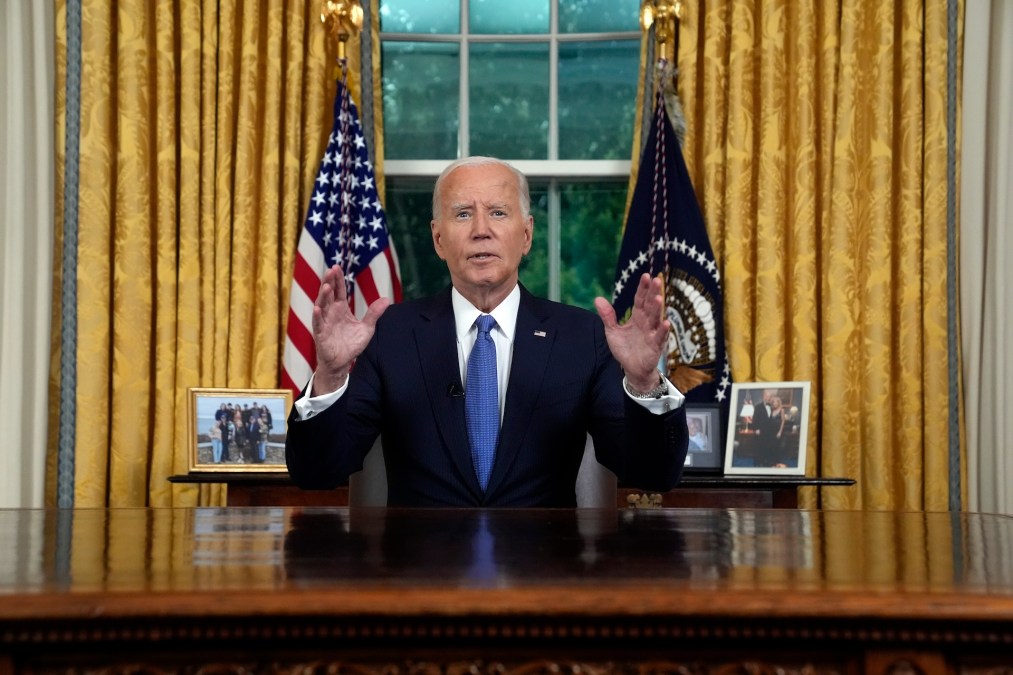

Here’s how the very top Biden administration cybersecurity officials and outside experts assess the momentous transformation, from interviews primarily conducted before Biden announced he wouldn’t run for a second term.

How it came to be

The shift began, at least in part, before President Joe Biden even took office. Anne Neuberger, the deputy national security adviser for cyber and emerging technology, had served at the National Security Agency prior to Biden’s election and didn’t like the arc of cyber defense.

“I came into it long believing that a voluntary approach to cybersecurity just hadn’t gotten enough outcomes,” she said, recalling the pre-Biden years. “We’re still seeing the same pretty basic cyberattacks. The number then had just exponentially increased, and we were still doing the same things. So I certainly came in feeling like we had to do a better job. And frankly, almost every country around the world was already doing it, putting in place minimum requirements.”

The Biden administration quickly drafted an executive order, leveraging the enormous purchasing power of the federal government to sway industry improvements among contractors and indirectly across the private sector. But by the summer of 2021, momentum for increased industry regulations grew following cyberattacks on Colonial Pipeline, which sparked a fuel panic, and the meat processing company JBS, which threatened the meat supply.

“It absolutely had a major impact,” Neuberger said. The Colonial Pipeline attack garnered attention from the president and spurred Homeland Security Secretary Alejandro Mayorkas to issue security directives for the top pipeline companies in the United States through the Transportation Security Administration.

“That was a big shift in the U.S.,” Neuberger said. “So after Colonial Pipeline, where people were saying, ‘How is this possible? How could a major regional pipeline be taken out by a group of criminals?’ And the answer was, ‘We have no cybersecurity standards, even though this is a major company which impacts millions of Americans, if a pipeline has to be shut down.’ So that certainly led us to say, ‘Well, let’s really look to see what kind of emergency authorities exist.’”

An accounting

The TSA pipeline rules begat others from the agency on air and rail carriers. Other agencies followed, varying in scope from the Securities and Exchange Commission’s disclosure rules for all publicly traded companies to the Federal Communications Commission’s move to protect an obscure but important backbone of the internet.

In 2022, Congress passed and Biden signed legislation requiring critical infrastructure companies to disclose major cyberattacks to the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency. In early 2023, the national security strategy, led by the Office of the National Cyber Director, outlined the goals.

“Individuals, small businesses, state and local governments, and infrastructure operators have limited resources and competing priorities, yet these actors’ choices can have a significant impact on our national cybersecurity,” the strategy states. “A single person’s momentary lapse in judgment, use of an outdated password, or errant click on a suspicious link should not have national security consequences. … Instead, across both the public and private sectors, we must ask more of the most capable and best positioned actors to make our digital ecosystem secure and resilient.”

Accompanying the standards were policies with similar goals, including additional executive orders covering other technologies or sectors, a voluntary program encouraging secure software design and a cybersecurity labeling initiative similar to the Energy Star program.

How it’s going

In leading the “Secure by Design” initiative, CISA was driven by a recognition of long-term trends, said Jen Easterly, director of the agency.

“Over the past four decades, from the creation of the internet to the mass adoption of software, we’ve witnessed a technology revolution that has forced safety and security to take a back seat where technology manufacturers and software producers are prioritizing speed to market and features over security,” she said. “Our vision is a future in which damaging cyber intrusions, in which ransomware attacks are a shocking anomaly.”

Since CISA kicked off the initiative in 2023, nearly 170 organizations have signed pledges, which Easterly said is one sign the initiative has “tapped into the zeitgeist.” However, she noted that this shift in thinking may take time to take root, similar to how Ralph Nader’s push in the 1960s for seatbelts and airbags in automobiles took decades to become widely accepted.

“This is a major cultural shift,” Easterly said. “I think it will take longer to really have an impact.” She added that it will also need more data, which CISA will eventually collect under the cyber reporting law known as CIRCIA.

Perhaps an even more distant goal touches on the same subject: shifting legal liability for cyberattacks to software makers. “Software makers are able to leverage their market position to fully disclaim liability by contract,” the national cybersecurity strategy states. It’s an area that National Cyber Director Harry Coker has identified as one of the hardest problems his office is working on, including via convening academia earlier this year to discuss concepts as a “starting point,” he said.

Coker isn’t satisfied with the progress in shifting the burden. “If we look at the National Cybersecurity strategy and what we call for entities, individuals and collectives to implement, and if you look at policies that are in place — if we all did all of that, there would be a heck of a lot less intrusions, but we’re not getting it done,” he said.

Neuberger also wants to see more. “What we’re doing is long overdue. I wish we’d go further,” she said. “We try to meter it to say … the threat is high. We’re low. We’ll raise it to medium eventually. We really need to get to where our defense is, at the very least, rapidly finding and pushing out offense. Now we’re not there yet. Now we’re doing the absolute minimums to make it just costly and harder for attackers.”

The Private Sector’s Response

Not everyone has embraced the administration’s approach, especially regarding minimum standard regulations. While some in the industry have been critical, the private sector has softened its opposition in particular areas after agencies have made changes in response to their complaints. Yet, a lawsuit from Republican state attorneys general derailed planned Environmental Protection Agency water security rules, and some GOP members of Congress have registered objections to specific agency standards.

“I would say that the administration and its agencies with their cyber regulations have done more harm than good,” said Rep. Andrew Garbarino, R-N.Y., who chairs the House Homeland Security subcommittee on cybersecurity. The series of rules sometimes leads to a company needing to report incidents to one agency in 12 hours, another in 48 hours and another in 72 hours, he said.

Garbarino specifically praised Easterly, but criticized how CISA is implementing the rule — also a common sentiment in industry. Ultimately he said his intent with the incident reporting legislation was to make reports to CISA the main rule, not just one of many. “There are too many regulations that are happening, and there’s no harmonization,” he said.

Coker said he’s grateful for Senate legislation that would set up a council on harmonization led by his office, because it’s another tough problem he wants to address. Easterly touted CISA’s solicitation of industry feedback on the incident reporting law, going as far to extend a comment period. Both said they have extensive communication with industry on their work.

Neuberger agreed, adding that outreach must balance the threat with the cost, aiming for an “aggressive, but achievable” bar for each sector.

On the other hand, opposition might have made the administration too timid, as seen with the sidelined EPA rule after the lawsuit.

“It was a light touch,” Allan Liska, a senior intelligence analyst at Recorded Future said of the EPA rules. “This is basic hygiene stuff; they weren’t asking anything overly complex, and immediately that got sued.” It’s possible other agencies have avoided taking stricter action, he said, even in the face of disparities over who has reported incidents to the SEC.

The administration’s ability to regulate industry is further complicated by a Supreme Court ruling that overturned the “Chevron doctrine,” which held that the courts should be deferential to the executive branch on interpreting federal law not specified by Congress.

“We’re still analyzing that and coming up with an approach,” Neuberger said.

Suzanne Spaulding, a former top cyber official who led the predecessor to CISA, credited the administration with major shifts, particularly in restructuring federal institutions to handle cyber. But the other “really important shift that they’ve done is they’ve moved in a serious way to look at, how far can the market take us? And how do we make it better?” said Spaulding, now senior adviser on homeland security at the international security program at the Center for Strategic and International Studies.

Spaulding highlighted the administration’s progress in secure by design and its implementation of the incident reporting law.

But overall, she noted the administration is “trying to drive the market to be more effective, because we know that’s the best way to try to do these things, if you can. And then recognizing the limitations of the market and having the courage, if you will, to step out and regulate where regulation is needed.”