Why Eugene Kaspersky keeps talking about ‘Project Sauron’

Kaspersky Lab founder and CEO Eugene Kaspersky says he’s figured out why the U.S. government hates his company.

According to Kaspersky, his company’s research into a sophisticated, international cyber espionage operation that targeted government entities in Russia, Iran and Rwanda represents why the Russian anti-virus maker has become a bogeyman for the U.S. government.

This reasoning came during public comments Kaspersky made Tuesday during a small event in London. His comments are the most detailed effort among Kaspersky’s multiple attempts to defend his company from allegations the Moscow-based company acts as an intelligence collection tool for Russian spies.

Kaspersky talked about his company’s discovery of U.S. intelligence related hacking operations, including those of the NSA-linked “Equation Group” and CIA-linked “Lamberts,” being the reason for the recent firestorm. He specifically emphasized the unveiling of one particular campaign — known as ProjectSauron or Strider — as a driving factor while also implying U.S. involvement with the discovered activity.

Researchers say Sauron mostly broke into a mix of military and governmental organizations. Victims included a slew of different groups around the world from an embassy in Belgium to an airline in China as well as several foreign internet service providers. There are less than 40 known victims of Sauron, which researchers say shows how narrowly focused the hackers are.

Based on publicly available research, it’s not clear how or if Sauron is connected to U.S. intelligence. When CyberScoop asked Kaspersky how he came to this conclusion, he said the attribution “comes from other experts.” A follow up question about who these experts are went unanswered.

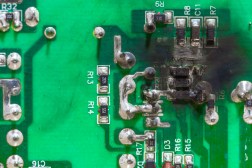

A powerpoint slide presented by Mr. Kaspersky at Tuesday’s event.

In terms of what could be achieved with the malware, Sauron had few equals, said Vikram Thakur, technical director of threat research with U.S. cybersecurity giant Symantec.

“We only come across this sort of really advanced threat so often,” Thakur said. “It was pretty clear from the beginning that they weren’t motivated by money, they weren’t trying to steal intellectual property I can tell you that…this was for intelligence.”

The most notable research published on Project Sauron was done by Kaspersky Lab and Symantec. The two firms published reports one day apart in August 2016.

In at least one known case, evidence of Project Sauron was found on a target that had already been infected with “Regin” malware, according to Symantec. Regin malware, based on classified documents leaked by NSA whistleblower Edward Snowden, is used by spy agencies in the Five Eyes nations — which includes the U.S., Britain, Canada, Australia and New Zealand.

Two former U.S. intelligence officials said Project Sauron was not the work of a U.S. intelligence agency, as Kaspersky seemed to imply, but rather an allied country. They declined to provide further details, however, and would only speak broadly on the topic and under condition of anonymity.

Neither Kaspersky nor Symantec has captured activity it attributes to Sauron since the original reports were made public. The hacking group seemingly disappeared overnight.

“Since then we haven’t seen them. They might still be active, but we haven’t yet associated any new malware families with Strider,” Thakur explained. “It’s likely because Strider either totally abandoned the project or changed their codebase so much that they look very different today … these types of national espionage-focused groups are difficult to track … you will only see a small piece of their activity.”

The 2016 disclosures likely burned some of the project’s high-end tools, some of which appear to have been in development as far back as the mid-2000s, according to Cameron Camp, a security researcher with cybersecurity firm ESET.

Thakur told CyberScoop that the group behind Project Sauron reacted to this exposure by attempting to cover their tracks.

“Even before we came out with research about Strider, not that long after a customer came to us with the original file, they started uninstalling their malware from all the victims we knew about,” Thakur said. “By the time we published anything they were totally gone.”

Tracking a ghost

In practice, Sauron operations have been largely tied to a stealthy, single variant of malware known as “Remsec,” which has been found on a small subset of victim networks.

Researchers noted Remsec appears to carry a modular design, meaning it was likely deployed as part of a larger exploitation framework that contained various hacking capabilities or “modules” — including the ability to steal emails, software certificates and encryption keys as well as record, scan and control domains, keystrokes and confidential files.

“The malware is unlike 99 percent of what we see,” Thakur said. “The architecture and sophistication is so comprehensive.”

One of the modules attached to Remsec, found by Kaspersky Lab, allowed for the search of specific files and documents on infected computers. The search conditions were set to look for material labelled as “Secret” and also in Italian, “Segreto.” Other keywords and terms were also flagged by the malware, including “code” and “usercode.”

The feature seems notably similar to what Kaspersky Lab’s own software has been accused of doing on behalf of Russian intelligence services. According to unnamed U.S. intelligence officials, Kaspersky Lab’s anti-virus engine was at one point manipulated to search for classified U.S. documents on computers that had Kaspersky Lab’s products installed. In one reported case, a former NSA contractor uploaded classified documents to his home computer which in turn fed them back to Moscow, according to The New York Times.

Media reports have suggested that the discovery of this supposed keyword search program in 2015 is one of the primary causes for the current Kaspersky Lab controversy. The Department of Homeland Security mandated in early September that federal agencies find and uninstall Kaspersky Lab software wherever it exists.

Another rare component evident in Remsec is a peculiar module that allowed for stealing information from air gapped networks. Airgapped environments are purposefully disconnected or segmented from the internet in order to guard against external cyberattacks. It’s common for sensitive military or intelligence databases to be airgapped.

This “special module [was] designed to move data from air-gapped networks to Internet-connected systems,” Kaspersky researchers previously noted. “To achieve this, removable USB devices are used. Once networked systems are compromised, the attackers wait for a USB drive to be attached to the infected machine.”

Airgapped malware can be successfully deployed in a number of different ways, but it traditionally requires a human being inserting a booby-trapped USB stick into a computer.

The other most famous case of air-gapped malware being used in the wild involved a complex, multi-stage cyberattack associated with U.S. intelligence, which is known as “Stuxnet.” With Stuxnet, another equally skilled hacking group used malware to sabotage Iran’s uranium enrichment program. Classified U.S. documents published by Wikileaks suggests that Stuxnet was the work of Equation Group.

An inspection of Equation Group’s toolset provides some limited connections to Sauron. But while the two groups appear to be comprised of english speaking operators, there’s very little evidence to conclusively link Sauron to any other entity.

“There not enough to conclusively connect them to Flame, Duqu, Equation or any of these other sort of similar operations,” said Thakur.